Humpback Whales: the Ocean’s Big, Friendly Giants

Here in Iceland, we are home to 12 species of cetaceans – whales, dolphins and porpoises. This includes magnificent species such as the blue whale, bottlenose whale, pilot whale and killer whale. Here in our part of Iceland, Faxafloi Bay, we see more regularly harbour porpoises, white-beaked dolphins, minke whales, and humpback whales.

The largest species that we have most frequently in the bay is the humpback whale, the 6th largest whale to exist today. However, we have been visited by a blue whale back in 2018! Who knows if that could happen again? Humpback whales can grow up to 18 m in length and weighing 40 tons! That is only 1/5 of the weight of a blue whale! Humpback whales can be found in every ocean, all around the world, from Antarctica to Australia, the Caribbean to Hawai’i, to Alaska and India. This doesn’t cover it all! They are so vastly spread.

Humpback whales during whale watching tours

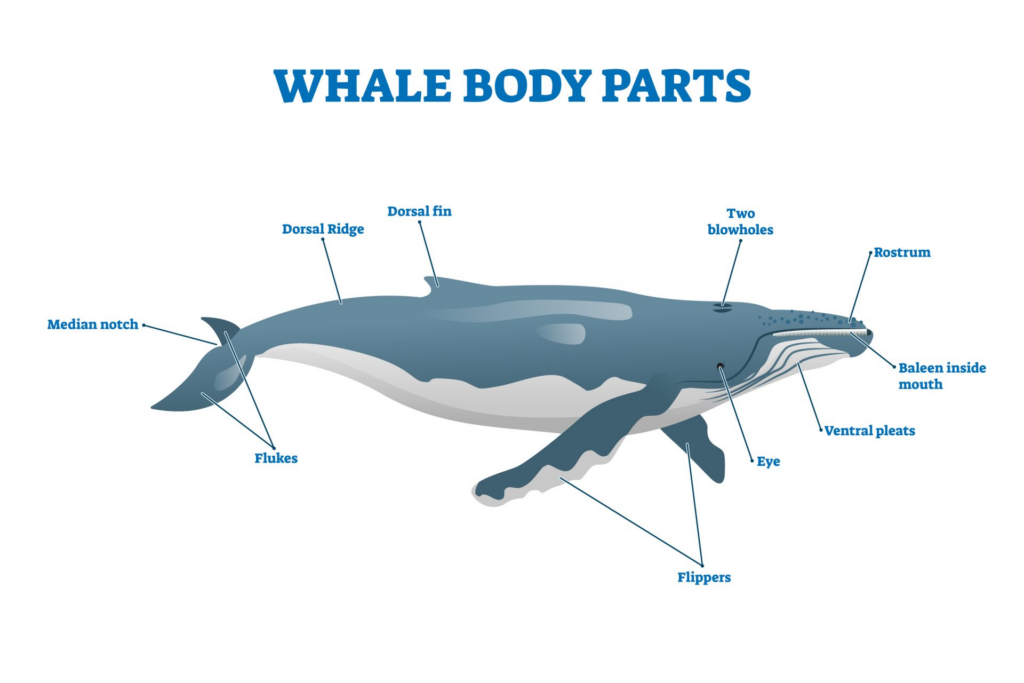

Humpback whales are one of the most prominently seen whale during whale-watching tours world-wide due to certain characteristics and features. As a marine mammal, cetaceans breath the oxygen out of the air just like we do, and also have lungs, not gills! For all cetaceans, the blowhole (nostrils) is now on the top of their head, and so when they come to the surface to breath, they let out a big cloud of air and water vapour. This can go up to 3m in height and can be seen from several kilometres away. They have mostly black bodies, with variations of white in different parts of the world. The humpback whales here in Iceland have white pectoral fins, whereas in the south and other regions, they have black ones. These pectoral fins can grow up to 1/3 of their body length, making them the largest of any cetacean. Their Latin name, Megaptera novaeangliae, means big winged of New England. They have extraordinary tails as well, which propel them through the water as they swim, growing up to 6m in width!

Humpback whales in Iceland

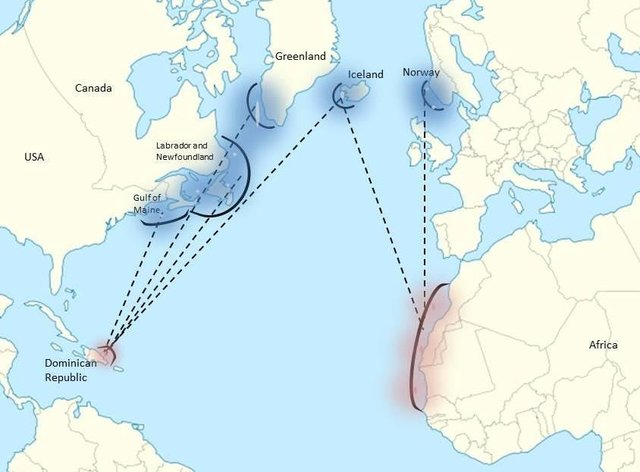

During the months of May to October, humpback whales will migrate to our waters so that they can feed! They travel between the warmer waters in the winter and these colder waters for the summer. Iceland is well known for their fish, and the humpback whales have learned that too! They will feed here until they have built up their fat reserves (blubber layer) so that they can fast on their migration back down south. The longest migration for mammals is made by the humpback whales that travel between Antarctica and northern South America, totalling to about 8,000 km. Hence why they have to spend so long feeding! There is more evidence, however, that humpback whales are starting to stay during the winter months as well. Not only here in Iceland, but several places around the world. Here in Iceland, we have had several individuals for the last few years, staying closer to shore, feeding every day near our islands.

Around Iceland, these humpback whales will be feeding on small shoaling fish like capelin, sandeels, and anchovies. As a type of baleen whale, humpback whales have these baleen plates which hang from their upper jaw! They’re made out of keratin, so just like what we have in our finger nails and hair, and make up a rigid hair-like structure, which acts like a sieve to filter the water. Although a lot of feeding occurs under the water, more times than not, we can see some feeding activity at the surface. This includes lunge feeding, bubble-net feeding, and the use of their pectoral fins to scoop the fish into their mouth. They also use the seafloor and shallower areas to trap the fish, making it easier to engulf them. To maintain their huge size, humpback whales have to eat up to 3,000 lbs of fish a day, that’s roughly the same weight of a female hippo! Out of the 16 species of baleen whales, half of them are also classified as rorqual whales. This means that the underside of their lower jaw is pleated so that it can expand when they are feeding.

Everyone that comes whale-watching with us gets so excited whenever we see humpback whales! They are one of the most acrobatic and active species, despite their huge size, we do often get to see them jumping out of the water (breaching), rolling around, slapping their pectoral fins or tails, and peduncle throwing (where they throw the lower half of their body out of the water). It is quite rare to see these behaviours all of the time, especially breaching, which can take up as much energy as 40 hand grenades blowing up!

However, when we are lucky enough to witness this beautiful display, it could be for a variety of reasons. Here in Iceland, the main reason that humpback whales breach could be mainly for fun! They could also be using the impact from their body to shock and kill fish, making it easier to feed. Humpback whales are also prone to sea lice, and so breaching could therefore be a way to remove these (unfortunately they don’t have fingers like us to be able to scratch!) Lastly, more commonly seen in breeding areas, breaching could be used to display their size and be using it for competition, specifically between males.

Males are also well known for their beautiful songs that they use to attract a mate. These songs will be made of whistles, low moans, howls and cries, and can also change over time. It’s also be found that calves can whisper to their mothers, as not to be heard by predators or … Humpback whales will reach sexual maturity between the ages of 4-10 years old, and then at 10 years old they will also be fully grown.

Females will be birthing one calf every couple of years, and these calves are only about 4-5 m in length, and weigh between 1-2 tonnes. The gestation period for a humpback whale is 11.5 months and a lot of care is needed to make sure that the calf survives.

As mentioned earlier, humpback whales migrate to Iceland during the summer months to feed. The other half of the year, they are breeding and having their calves in the warmer waters of the Caribbean and Cape Verde. This is a 6,000 km journey that they have to make and will take them a few months to complete. These tropical waters have many benefits as opposed to giving birth in Iceland.

First of all, the cold waters of Iceland wouldn’t allow the calves a good chance of survival, as they are not born with a thick enough blubber layer. They will spend their first year of life feeding their mothers milk, and are often seen swimming side-by-side with their pectoral fins touching. The second reason is that these warmer waters are safer from predators, especially the killer whales, which can eat up to 5 humpback whale calves a day. After using shallow waters for protection, the mother and calf pair will take to open water once the calf is ready to migrate. This is when the calf is most vulnerable to being a target. Hopefully, if they survive the migration, they will then remember this route and continue going to the same breeding and feeding areas that their mother has taught them.

These humpback whales are not short-lived, they can grow up to 90 years old. There has been a lot of research put into humpback whales as they are an easier species. A lot of the research has involved tagging and tracking, which although for a short period is safe for the whale, but an even better approach is the non-invasive method of photo-identification. This is where you just use photographs of the whale, specifically their dorsal fin and fluke. Due to scarring, the colouration, and patterns on their fluke, we can ID each individual humpback whale. The trailing edge of the fluke is also used to ID them.

Being able to estimate their age, understand their migration routes, and interactions with boats, we are able to conserve the species by better understanding them. Although their population numbers are stable, humpback whales were once threatened by whaling by the mid-1900’s. The species was almost driven to extinction, until humpback whaling was banned in 1963. Although this has been a huge success, they are still facing threats in the modern world. Most of the larger marine animals are threatened with pollution, vessel strikes and traffic, entanglement and climate change. Noise pollution in particular can disrupt their ability to communicate and forage, and climate change has many impacts on prey distribution, sea temperature, ice coverage, and diminished reproduction.

Two photos of humpback whale flukes, highlighting the differences that occur between fluke patterns, colouration and scars. Taken on-board by Rebecca Roberts

Don’t be discouraged just yet! There is still time and hope for everything to get better! Try searching organisations that are contributing to the conservation of humpback whales and donate to their cause. If you want to get more involved, try organising a beach clean-up to get rid of plastic and other rubbish before they end up in the sea! Companies like The Ocean Cleanup are creating technology that collects plastic pollution out at sea! Continue to educate yourselves about the ongoing problems in the world, and try your hardest to be the best version of yourselves! These blogs have a few ideas that you can try implementing in your life: https://awionline.org/content/what-you-can-do-marine-wildlife and https://www.ifaw.org/international/journal/fifteen-ways-protect-the-ocean-marine-animals

By Rebecca Roberts